Migrants as accidental environmentalists

This blog was originally posted on Medium.com in April 2021

EeMun Chen, Managing Director of Ethnic Research Aotearoa and an evaluation and research specialist from MartinJenkins, argues that we don’t yet know nearly enough about how cultural context shapes people’s environmental attitudes and behaviour – and therefore about how behaviour can be influenced to tackle the global waste explosion.

An image has stuck in my head from one day in 2009 when my relatives from Malaysia came to stay with my parents in Christchurch for my brother’s wedding: I went into the guest bathroom at one point to find three plastic yoghurt pottles each with a toothbrush standing up in it.

Although Malaysia is a developing country, my relatives are reasonably well-off, and I know that my parents had a bunch of cups in the kitchen they could have used instead. So is this full-on, environmentally conscious ‘re-use’ in action? Or is something else going on?

My conclusion after canvasing some of the available studies of environmental attitudes and behaviour is that, in fact, we’re not sure what’s going on in this area. This has to be a significant knowledge gap when it comes to designing strategies to influence behaviour to tackle the waste problem and move New Zealand up the layers in the waste hierarchy – from recycling to the more advanced levels of re-using, replacing and refusing.

Cultural context has been ignored

The initiatives we’ve talked about in previous articles in this waste series all require changes in behaviour – by individuals and households, by manufacturers and other businesses, and by government agencies and NGOs.

The Government has made some structural and policy settings more conducive to diverting waste items from landfills, and we are seeing signs of ‘rethinking’ the way our system of production and consumption works. But shifting attitudes and behaviours at both the individual and collective levels is going to be critical.

There’s quite a bit of research into the types of messages and channels that public campaigns and education programmes need to focus on in order to change consumer behaviour – such as appeals to concern for the environment, or simple altruism. However, a critical component that a lot of this research misses – and especially important for New Zealand – is the influence of cultural context, intercultural differences, and migration.

The research has focused on WEIRD populations and cultures

In 2018, 60% of people living in New Zealand on Census night indicated they were ‘European only’, and in Auckland this figure was only 45%. Projections from Stats NZ suggest these percentages will fall rapidly in the next 20 years.

But a lot of the research in psychology and other social sciences suffers from most participants being from ‘WEIRD’ cultures – that is, Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. In one of the major, revered psychology journals, Psychological science, more than 90% of studies came from a set of countries that represent less than 15% of the world’s population.

While historically New Zealand would probably be considered a WEIRD country, our current and projected cultural make-up suggests that the carrots, sticks and sermons that will move us up the waste hierarchy are going to be as diverse as our people.

Non-WEIRDs as environmental guardians?

Non-WEIRD and indigenous peoples have long been associated with environment-friendly values and attitudes. The ‘Biophilia’ hypothesis, for example, is that humans have an innate need or propensity to affiliate with the natural world. But this propensity is often especially associated with non-WEIRD peoples, who are seen as living in greater harmony with the natural environment.

In other parts of the world the concept ‘Buen vivir’ is gaining some traction. This Spanish term loosely translates to ‘good living’ or ‘living well’. It is said to derive from the Quechua peoples of the Andes and their term ‘sumak kawsay’, which prioritises being community-centric, ecologically balanced, and culturally sensitive.

Buen vivir has some parallels with the Māori worldview on the interconnectedness of whenua, wai and tāngata. This key aspect of te ao Māori is beautifully expressed in, for example, the whakataukī ‘Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au’ – ‘I am the river and the river is me’.

But how has colonisation and urbanisation influenced Māori approaches to waste? It’s unclear to what extent Māori – particularly urban Māori – feel they are able to put kaitiakitanga (guardianship) into action or see it as important in their daily lives. I imagine that many Māori would say they’re unable to practise kaitiakitanga because they no longer have possession of their lands and taonga.

The statement from the Aotearoa Plastic Pollution Alliance on environmental justice and waste makes this point:

“APPA acknowledges that injustices against Māori, Pasifika, Black and Indigenous peoples, and People of Colour also extend into the areas of waste, pollution and ecological degradation. NZ has long treated indigenous and foreign lands as disposable, from the use of the Public Works Act to confiscate Māori land in order to construct landfills to the exports of our plastics and other waste to Southeast Asia.”

There are some fantastic grassroots initiatives, in highly urbanised Tāmaki Makaurau for instance, that are reconnecting Māori with kaitiakitanga. There’s the Para Kore ki Tāmaki (Zero Waste) programme, which works with marae and Māori organisations to educate and empower Māori to be kaitiaki (guardians) of Papatūānuku (Mother Earth) through a zero waste philosophy and waste diversion.

Non-WEIRDs as cavalier exploiters of the environment?

So there’s the view or assumption that indigenous belief systems are a positive force for environmental protection, including for diverting and minimising waste.

But there’s also another current of thinking that runs at least partly counter to it: the belief that ethnic groups other than ‘whites’ are less likely to be concerned for the environment because they tend to be poorer and less educated.

As Vincent Medina and others have explained, that view is based on the idea of the ‘environmental hierarchy of needs’ – this is an application of Abraham Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of needs’ as a theory of human motivation (this is often referred to as the ‘postmaterialist’ thesis, or the ‘full stomach’ phenomenon). The ‘hierarchy of needs’ says that individuals can’t begin to put their time and resources into problems of the world unless their basic material and physiological needs are met first.

Arguably, the common views among many New Zealanders about Asian immigrants and their environmental values appear to fit with the postmaterialist thesis. Immigrants from Asia have received media attention for what’s seen as their poor environmental values and behaviour, particularly the exploitation of marine life.

That may be a popular view, but in fact New Zealand research on immigrants’ environmental values and worldviews found no significant difference compared with those of the New Zealand-born population. So while Asian migrants may come from countries that have highly consumerist cultures and prioritise economic development over environmental sustainability, this research doesn’t support the view that Asian immigrants in Aotearoa have cavalier attitudes to the natural environment.

So how much do we know?

My reading of the research is that in fact we don’t know how far and in what way non-WEIRD groups are different from WEIRD groups – different researchers seem to have drawn different conclusions. We also don’t know how far non-WEIRD groups can be thought of as a homogenous unit and how much their experiences, environments and practices vary.

It seems though that so far studies and policy decisions have underestimated the power of context – particularly group norms, differences within groups, cultural orientation, and economic factors.

Researchers have been critical of the focus on the indigenous-settler binary. They’ve argued that new research needs to look at intercultural differences and the influence of migration and acculturation.

Lesley Head and two other Australian geography experts comment:

“[R]esearch on environmental values of migrants is scarcely developed … and migrants’ perspectives have been virtually ignored in climate change research….”

Subtle Asian Traits

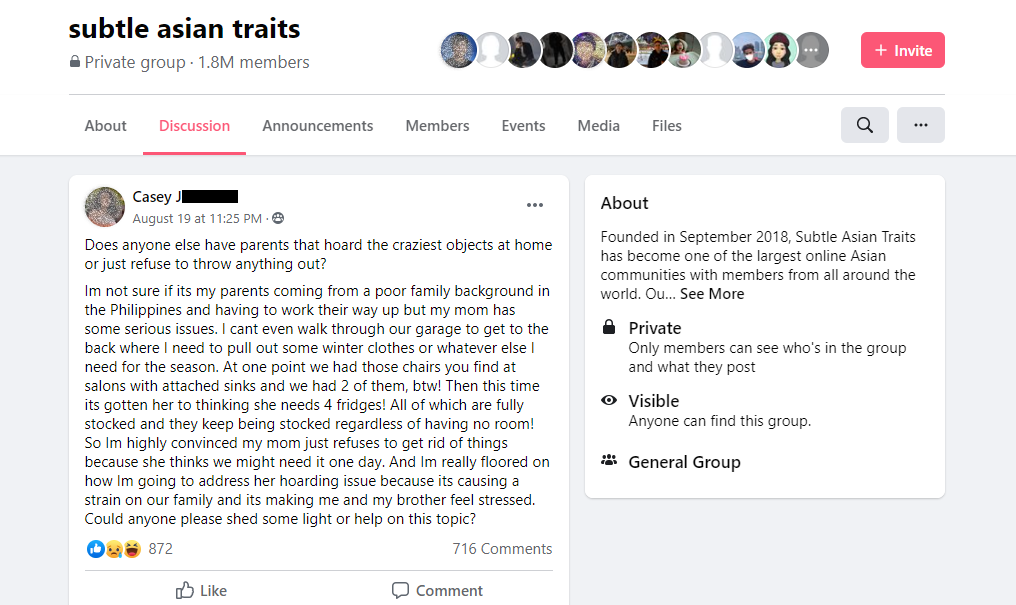

I belong to a Facebook group called ‘Subtle Asian Traits’, all about the struggles and joys of being a first-generation immigrant. Set up in 2018 by Asian-Australian high-school students, the group now has 1.8 million members.

The Subtle Asian Traits group features countless stories of mirth and frustration as parents and relatives hoard all manner of plastic containers, snap-lock bags, and potentially useful cardboard boxes. They seem to be completely unable to throw anything out.

Exasperation from one member of the ‘Subtle Asian traits’ Facebook group

Another member opens up their parents’ dishwasher

Another thread from the group begins:

“Just me, or do other children of immigrants feel guilty every time they use a Ziploc bag?”

This poster also added that ‘Of course our frugality is in constant tension with our germ phobia.’

Migrants as accidental environmentalists?

So, circling back to my vignette and my question at the beginning, is there a resource-conscientiousness thing going on here among migrants?

Lesley Head and her colleagues argue that the pro-environmental actions of migrants are often inadvertent – they may not want to be ‘green’, but the outcomes surely are. Because of this, they comment that (Western) frameworks of what it means to be ‘pro-environment’ may need to be re-written.

They note some other examples of migrant practices that have positive environmental effects, including:

Sri Lankan migrants refusing to buy a clothes dryer and doing line-drying in summer and in winter

An elderly Vietnamese woman washing herself with a bucket of water, and washing dishes by hand ‘the Vietnamese way’

Chinese migrants bringing pre-migration transport habits and preferences with them, and moving close to public transport routes

Bucket bathing by Burmese migrants

Some migrant groups continuing with less resource-intensive practices even when their incomes have increased.

So what’s needed?

Cultural context and migration have rarely been investigated in relation to waste, but clearly environmental campaigns and incentives need to take account of different values and norms in our population. They need to consider the environmental values, knowledge and behaviour of all types of New Zealanders, and specifically in relation to waste minimisation and diversion.

Migration, and length of time in New Zealand, appear to make a difference, and their influence is complex, nonlinear and variable. These factors may disrupt existing environmental values, knowledge and behaviour, or make migrants dig in their existing environmental heels.

Migrants in particular bring diverse ancestries, ethnicities, life histories, worldviews and behaviours, and the accepted findings from WEIRD-based research may well not apply. Migrants challenge traditionally Western conceptualisations of pro-environmentalism and how best to measure environmental behaviour.

Migrants’ behaviour as accidental environmentalists should be rewarded and leveraged. Designers of behaviour change campaigns need to ask how migrants as accidental environmentalists can be used to achieve change – including how they can be used as champions in their communities.

Gaining a more nuanced understanding of national environmental behaviour can also be valuable through dispelling common myths and misconceptions. For example, the New Zealand research I noted that found that migrants hold similar environmental worldviews to the New Zealand-born – a useful factoid to employ against environmental racism.

Photo by Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa on Unsplash